MAINSPACE EXHIBITION /

2 works, 3 talks, 6 questions

Eric Moschopedis with Keyede Osuntokun and Bryce Krynski

September 11 – October 10, 2015

Public Discussions

Talks are free and open to the public.

Placement and Displacement: Public Art and the Creative City in East Calgary

A talk and walk by Katie Varney

Sunday, September 13 at 2:00 pm

Meet at the Simmons Building (618 Confluence Way S.E.)

(approximately 1 hour)

Katie Varney is a cultural worker, designer, and recent graduate from the University of Calgary’s Communication and Culture master’s program. Her academic research looks at public art and its connection to urban development and gentrification processes. Join her on a guided walk and discussion about how the creative city script is playing out in East Calgary.

Dover Kids Club: Creating Grassroots Culture

A talk by Pam Beebe and Tito Gomez

Tuesday, September 29 at 7:00 pm

The New Gallery / 208 Centre St. S.E.

Started by Pam Beebe and Tito Gomez, Dover Kids Club is a grassroots youth initiative that seeks to create safe social spaces for the children that live in and around the community of Dover. Since its founding in September of 2014, Dover Kids Club has hosted different social events, spoken word and poetry workshops, and is working with the Greater Forest Lawn Senior Centre and Native Network’s youth program to create cultural opportunities within their community. Joining them will be spoken word artists and collaborators Wakefield Brewster and Jenny Chanthabouala. Come hear their story.

There is No Future, Yet: A Conversation between Hye-Seung Jung and Eric Moschopedis

Tuesday, October 6th at 7:00 pm

The New Gallery / 208 Centre St. S.E.

Hye-Seung Jung is a visual artist based in Calgary, Canada. Her art practice involves an observation of built-environments. She asks how societal values are embedded in these spaces and how, for instance, spaces relate to human interaction, a sense of belonging, and the creation of culture. In consideration with geographic and cultural contexts, Jung explores the themes of place, a sense of community, and spirituality. In July, Hye-Seung Jung and Eric Moschopedis sat down to have a conversation about artists, the city, spaces, economics, and cultural policy. They have been meeting regularly ever since to share information, wrestle with contemporary culture, and at times imagine possible futures. Come sit in on one of these conversations and add a voice.

On 2 Works, 3 Talks, 6 Questions by Eric Moschopedis (with Keyede Osuntokun and Bryce Krynski)

In his book The Rise of the Creative Class, guru Richard Florida famously proposes that economies are recentering around the appearance of a new economic class: the entrepreneurial free-agents of the “creative class.” In a way, the figure of the creative class with its aptitude for immaterial labour and its supposed desire for more flexible working conditions seems perfect in a post-Fordist, globalized moment where material factory labour has been moved across the globe by corporate bodies chasing greater profits through the frontier logic of uneven development. In separating creative work from factory and service work via the rubric of class, typically used to describe economic hierarchies, an unaware Florida ends up reproducing inequalities around race and gender, tapping into concerns over the exporting of production and the importing of migrant labour.

Working at this uncomfortable junction point between artistic production and the different and uneven subjectivities produced in and by the city, Calgary artist Eric Moschopedis’ playful practice focuses on performative and relational work that not only experiments with the way that people connect to and interact with each other, but also performs research into the ways those relations produce shared space. Largely working with collaborators (particularly his partner Mia Rushton), Moschopedis’ oeuvre asks its participants to find ways to produce the city otherwise, collectively mapping a neigbourhood (in Imaginary Ordinary and Council of Community Conveyors), treating the city like the shared space of a library book (in Each Other), or foraging for local plants to measure them against class differences (in Hunter, Gatherer, Purveyor). At the same time, the collaborative creativity Moschopedis asks of his participants intersects with the drive to incorporate creativity as an economic force to enliven the city. In other words, how critical is foraging for local ingredients when gentrifying entrepreneurs are doing the same, only to be served in their boutique restaurants alongside local craft beers? How can art stand as a critical intervention in a structure that treats it as another economic driver?

Bringing these concerns into the gallery space, the twinned collaborative works of Moschopedis’ 2 Works, 3 Talks, 6 Questions both critique the flattening out of difference in precisely this neoliberal and post-political moment where creativity and innovation turn economic. Taking the discourse around the creative city to task, Moschopedis and Keyede Osuntokun’s where our secrets meet and other derivatives of losing affectively reacts to Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class, interrogating the texts that help code the production of our shared spaces. Facing the intersection of race and class, Moschopedis and Bryce Krynski’s 10 portraits of people in gold face captures ten portraits of individuals from different backgrounds and subject positions who sit, eyes closed, their racial differences effaced by gold paint that reduces each to an individualized economic actor.

Taken together, these pieces articulate a complex set of problematics about the value of creativity, and of artistic critique, in a version of the city that only values profit-generation. In his essay “How High is the City, How Deep is Our Love?,” Jeff Derksen asks how we might practice artistic critique in a post-Florida world. He suggests that strategies like Florida’s “try to take the very aspects that we love about the city – street life, alternative modes of production, mobility, and movement by choice – and incorporate[s] them into an economic force at the same time as it blunts artistic critique aimed at capitalism and everyday life” (39-40). What is left for artistic critique after it has been captured by what it hates? Moschopedis and Osuntokun overcode Florida’s text, inscribing their careful responses and gut reactions directly on it. In the process, they open up critical reading and affective response as forms of knowledge production that begin to untangle the neoliberal codes through which we organize and build our cities and communities. What if we start with critique, they seem to ask.

Moschopedis and Krynski’s 10 Portraits reacts to this question by posing the production of subjectivity (of race, gender, sexuality, class, and ability) under capitalism and neoliberalism as central to the problem. Each portrait presents a different person in “gold face,” their identity reduced to a symbolic representation of their value as an independent economic actor. But the gold paint fails to obscure the face of each subject – a white man still a white man, a black woman still a black woman. In this failure, Moschopedis and Krynski also dramatize the failure of post- discourses (post-race, post-feminism, etc.), arguing that attempts to erase difference (and the extreme social and spatial inequities that accompany it) only serve to grease the wheels of economic production and prop up ugly white supremacist and patriarchal structures. Within the frame of artistic critique, they ask what other things artists complicit with the connection of creativity and economic value might also be complicit with. In a historical moment where powerful movements have emerged around race, gender, and sexuality – Idle No More, Black Lives Matter, ongoing critiques of harassment and rape culture, an increasing acknowledgement of trans issues, etc. – how might we imagine more creative and critical cities that seek to crack apart the codes that allow us to unevenly organize in unjust ways? And how might we imagine new social and spatial processes and forms that don’t just reproduce injustice?

– Ryan Fitzpatrick

Derksen, Jeff. “How High is the City, How Deep is Your Love.” After Euphoria. Dijon, France: Les Presses du Réel; Zurich: JRP|Ringier, 2013. 26-43. Print.

Florida, Richard. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic, 2002. Print.

Florida, Richard. The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic, 2002. Print.

Biographies

Eric Moschopedis is an award winning interdisciplinary visual artist, facilitator, and community organizer. During the past decade he has developed an exciting catalogue of community-specific and participatory works that operate in both a gallery and post-gallery context. His practice uses public space, participation, intervention, and performance to interrogate local day-to-day life. As a visual artist, his work crosses disciplinary boundaries and utilizes a number of materials and processes. He brings together elements of craft, performance, printmaking, and cultural geography, to create playful, but highly critical projects. This approach has harvested presentation, workshop, lecture, and publication opportunities in Canada, the United States, and Europe—largely with his long-time collaborator Mia Rushton.

Bryce Krynski is an independent photographer who began his photographic practice while studying journalism at SAIT. Since graduating he has shot and produced editorial images for national magazines and newspapers. Moschopedis and Krynski have worked together intermittently for well over a decade. In the late 1990s they co-authored a short surrealist play entitled “Pillage and Cover” (1999), that had a short run in the UK. More recently, Krynski has worked with Moschopedis and Mia Rushton regularly to collaboratively document their ephemeral works in Alberta and internationally. For 10 Portraits… Krynski and Moschopedis worked closely to develop the project from concept to its present form of representation.

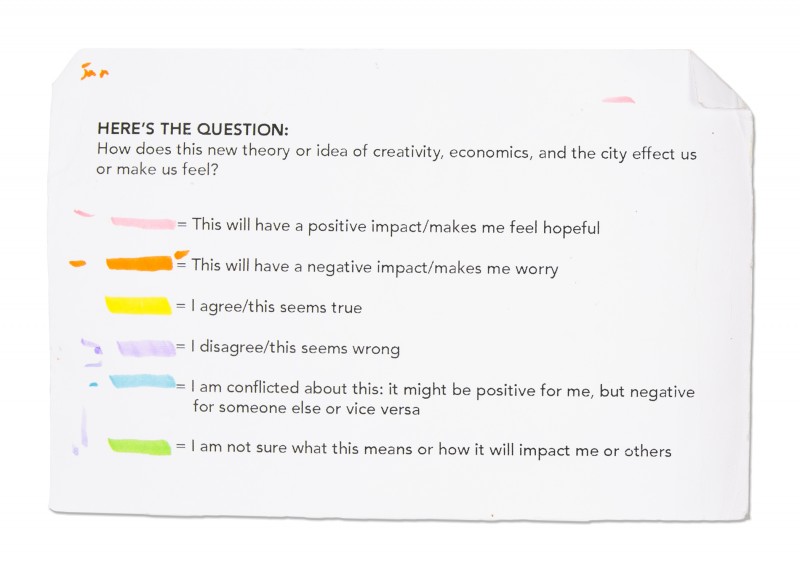

Moschopedis met Keyede Osuntokun by chance in early 2014 at Bow Valley College Library (Keyede was a nursing student at the time and Eric works there). Osuntokun was carrying a copy of Richard Florida’s 2012 edition of Rise of the Creative Class. Moschopedis had long had the idea of highlighting the book based on a critical and affective criteria with somebody from outside of the arts community. Moschopedis and Osuntokun agreed to intervene into Florida’s toxic discourse by reading and studying their own copies of Rise of the Creative Class. Together they decided on a colour coded criteria in which to document their thoughts about the book. Over several months, Moschopedis and Osuntokun filled up Florida’s pages with highlighter ink and marginalia—inscribing onto the pages their own personalities, identities, histories, politics, and affects. Keyede Osuntokun is a graduate of Bow Valley College’s Practical Nursing program. Originally from Lagos, Nigeria, Osuntokun moved to Calgary in 2012. In addition to the creative arts, her interests include hiking, dancing, photography, psychology, and economics. She likes to volunteer and take care of people. Osuntokun is looking to become a pharmacist and a model. Keyede says this about working on the project: “This project helps to pull out things that you won’t necessarily think makes a difference in every day thinking, and also puts into perspective how economics shapes living, growing and adaption over the years and in various countries.”

Ryan Fitzpatrick is a poet and critic living in Vancouver (but originally from Calgary). He is a PhD Candidate in English at Simon Fraser University where he works on contemporary Canadian poetics after the spatial turn. He is the author of two books of poetry: Fortified Castles (Talonbooks, 2014) and Fake Math (Snare, 2007). With Jonathan Ball, he co-edited Why Poetry Sucks: An Anthology of Humorous Experimental Canadian Poetry (Insomniac, 2014). With Deanna Fong and Janey Dodd, he is working on the second iteration of the Fred Wah Digital Archive (fredwah.ca).